By Adiel Gavish

When I was in college, I had a professor named Mike. Professor Mike (who is still teaching at the University at Buffalo) taught Fluvial Geomorphology— the dynamics of how rivers and lakes change and evolve over time, on their own. He was the kind of teacher who was more of a person than a professor and treated students like peers, rather than pupils. His staple attire consisted of casual blue wool sweaters, with khaki pants and black New Balance sneakers, his hair askew in every direction, much like his lectures (which he often tried to pat down, but never stayed).

His mind was sharp, fluid and steady, yet constantly changing like a rapid current.

Professor Mike was brilliant and he loved to teach. Affable and easy going, class seemed more like a weekly fireside chat in physics and fluid dynamics (as if that’s even possible!). He loved sharing everything he knew. His brain worked at light speed, zigging and zagging from “a” to “3,″ and never quite landing but always bringing us back to the bigger picture. His mind was sharp, fluid and steady, yet constantly changing like a rapid current. I never stopped listening. In most of my classes I would drift into daydream, but not in Professor Mike’s. The weekly tangents were brilliant and enthralling. I learned the most when he went completely off topic and into various fractals and branches of cutting edge research, his own finely crafted theories, and of course, chaos theory.

The river had much to teach, and we had much to learn.

Professor Mike taught us that rivers and streams went through a complex process by which every input had an output— every action had a reaction— and every change in the physical structure of these fluid bodies resulted in the “organism” somehow correcting itself. He taught us that the river knew “how” — how to self-balance, how to optimize change, how to adapt and evolve, survive and thrive.

While writing a paper for class I realized that rivers were alive. Rivers, lakes, and streams were self-balancing, living entities, and if something like a river , without any management or third-party imposition, could sustain itself ad infinitum, then the river had much to teach, and we had much to learn. These natural processes of self-correction, adaptation, and eventual evolution were ancient practices . For example, rivers take the path of least resistance and follow Murray’s Law in order to optimize flow— could we learn from these patterns and naturally occurring strategies?

Rivers, lakes and streams were self-balancing entities — without any management or third-party imposition…

If a river can feel change upstream, which results in corrections downstream, and everywhere in between, there must be principles of self-equilibrium that can be extrapolated and applied to man-made systems as well, I thought. At first, I suspected we could apply these principles to something like a car manufacturing line, with multiple linear inputs and outputs and points of change. Then I realized there were multiple systems with complex sets and series of inputs and outputs that required the ability to automatically react and respond to external changes, such as businesses and buildings, and that these processes could be applied not just to the physical “thing” itself, but to the system as a whole — a living entity far greater than the sum of its parts.

It wasn’t until a few years later that I was introduced to the term “biomimicry.” A biologist named Janine Benyus had coined the term in her book. People were already doing this?! She was a scientist who was also a philosopher; a gifted observationalist with a brilliant mind that ebbed and flowed between the current reality of our man-made systems and the dynamic world it could be if we opened our eyes to the brilliance embedded in natural ecosystems.

These processes could be applied not just to the physical “thing” itself, but to the system as a whole — a living entity far greater than the sum of its parts.

From that point forward, the promise of biomimicry— innovation inspired by nature , the technology of biology , ancient strategies that are time-tested and nature-approved —colored every man-made challenge I saw.

A year later I was in a coastal nature preserve in Costa Rica for a week-long immersive with Janine and 30 other students and professionals from around the world who had also somehow come to the same conclusion— nature is teaching, it’s time we listen.

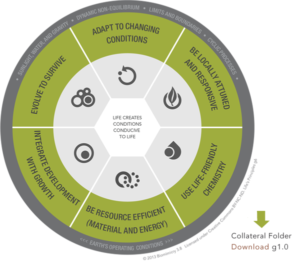

My colleagues (and now great friends) included kindergarten teachers from the midwest, high school students from Denmark, engineers from Boeing, designers from France, creatives from Kohler, and executives from GE. Janine and Biomimicry 3.8 co-founder Dr. Dayna Baumeister taught us “Life’s Principles” of innovation and design in the tropical rainforest and on the beach — the patterns, strategies and principles we can emulate and embed to “create conditions conducive to life.” Because at the end of the day, what else are we all working towards?

Recently, I did a quick search for Dr. Woldenberg and was surprised to read negative remarks a few students had given on his teaching style. No one else seemed to appreciate those wonderful tangents that lead to a theory that changed my life forever. To them it was an ugly chaos, not a beautiful, dancing mosaic of insights and discoveries cultivated over a lifelong career of careful observation, contemplation, and a deep understanding of natural phenomena —the patterns and processes that shaped the entire planet as we know it today. And it saddened me to read such negative, judgmental remarks.

In a world filled with not even 15 minutes, but perhaps the elusive promise of 15 seconds of fame, coupled with ever-shortening attention spans, it’s more important now than ever to slow our minds down for a moment, pause, and appreciate not how information is provided, but that wisdom is imparted in many beautifully diverse and fantastical ways.

Those who are capable of observing may not have the gift for presenting, but should we not open our minds to their knowledge and artistry all the same?

People often quote Einstein for having said, “You can’t solve problems using the same thinking that created them.” Solutions to our most pressing global challenges are everywhere (literally…outside). Brilliant thinkers cannot always give talks worthy of TED to make their points or inspire the next generation of innovators. Those of us who are more introverted (a trait many scientists share) may find public oration too intimidating of a platform — but should their insights and discoveries therefore go unnoticed? And unfortunately trees, with 3.8 billion years of sustainable design wisdom to bestow, cannot take to the TED stage either.

Professor Mike taught me to seek and appreciate the brilliance inside of everyone. He showed me that every-one and every-thing has something to teach, and something from which we can learn, grow, and gain. A slightly less-than-organized professor, a rambling brook, the tree outside your window, an entire mountain range … it’s up to us to find a way to listen.

This post was originally published on patternly.org.

About the author:

Adiel Gavish is the Social Media and Communications Manager for the Biomimicry Institute, which seeks to empower people to create nature-inspired solutions for a healthy planet. She is also the founder of the BiomimicryNYC regional network, working to spur nature inspired and mentored businesses and innovations by bringing a diverse network of students, designers and professionals together in the NYC metro region.