It’s been a consultant for NASA, shot at by police and mistaken for an alien. How slime mold–a brainless, single-celled organism–mapped the dark universe, keeps challenging the top minds to rethink what intelligence even is and has an ability to fill us with wonder beyond the human kind.

What does it mean when the most powerful and well-funded organizations, NASA to the United Nations, turn to a brainless blob for answers?

We tidily classify it as a primitive, no-brained, unicellular organism that gives us a glimpse of our past, and yet the most respected thinkers and institutions turn to it for innovations for our future. Not only that, they get tripped up about what intelligence even means if something without a brain can do things like calculate risks over rewards, remember dinnertime like clockwork and trace parts of the cosmos we can’t.

Their contradictions are as profound as they are widespread: Brainless and genius. Transparent and mysterious. Unicellular and universe. Repulsive and alluring. Simple and an enigma.

These masters of efficiency spread delight, wonder, shock, and humility across the globe with the same ease they ooze across a petri dish. As they make their way through our worlds, it’s clear why slime mold was the perfect choice for everyone from space agencies to school teachers, artists to architects, city planners to engineers, and kids to astrophysicists to turn to for a fresh perspective.

This visualization shows the CO2 being added to Earth’s atmosphere over the course of the year 2021, split into four major contributors:

fossil fuels in orange, burning biomass in red, land ecosystems in green, and the ocean in blue. Image credit: NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio

It’s obvious, but if we want to save the planet, or work towards one that resembles the blue marble that we inherited, we not only need nature, we need to look to nature.

We’re starting to get a sense of what the climate apocalypse means. While writing this article, skies turned orange, cities drowned, we broke multiple records including hottest day and hottest summer—and ultimately hottest year—on record. At times writing this series, going outside felt like walking in an oven. What’s ahead is worse. We are in the Anthropocene–an epoch defined by humans and the scars that have disfigured and imbalanced Earth. There are consequences when stuff produced by humans (cars, cement, clothing) outweigh stuff produced by nature (violets, elephants, coral reefs). We’re facing climate damages over $600 trillion (that’s all the wealth that exists today x two). Money can’t fix it. We need nature.

I guess our first question can be answered with a question: What is more competitive and elegant than evolution, or more packed with proof coated in possibility? A brainless blob that has stayed around for > 500 million years has proven to be insanely skilled at figuring out what works and what doesn’t. With biomimicry, we have the chance to get smarter and live better by transferring that knowledge to our lives. After all, a single cell guided the world’s top scientists through another universe and its only limitations were our own.

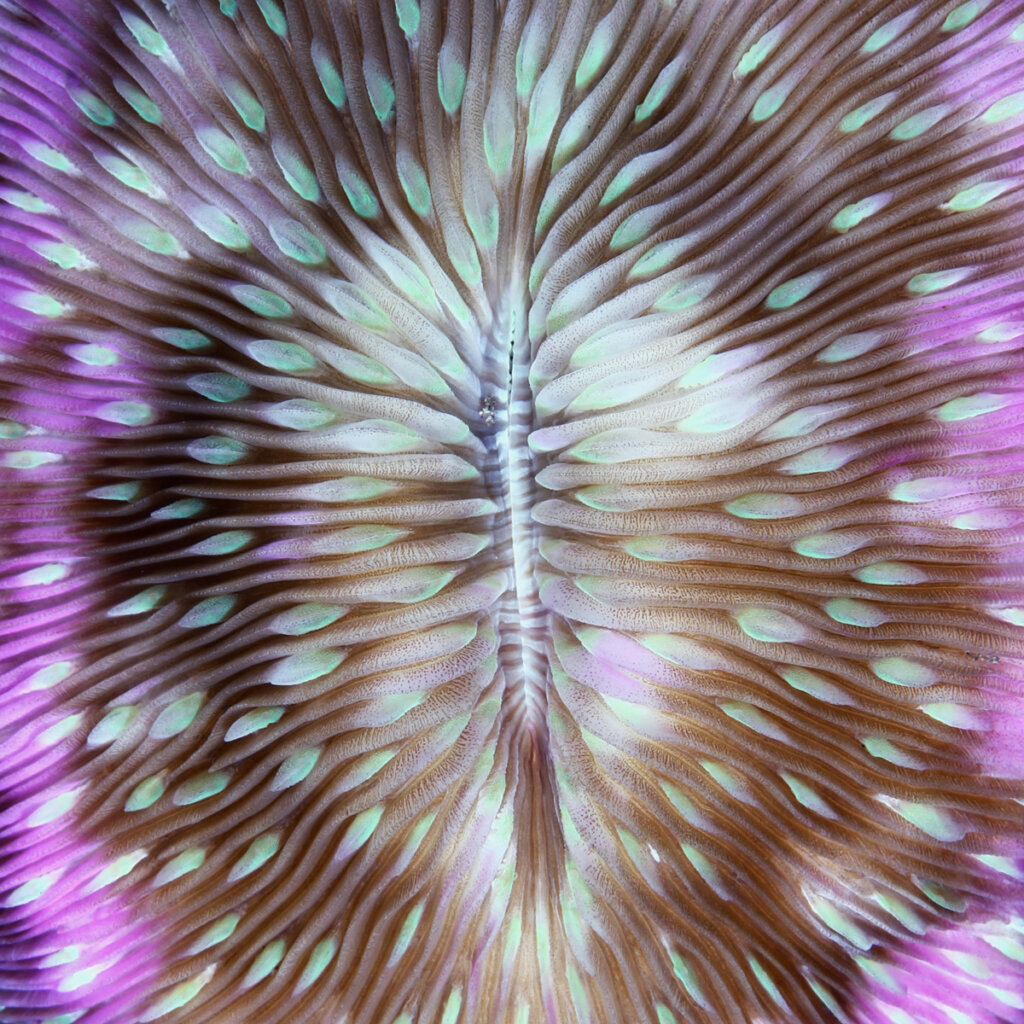

And beyond slime mold—what about other brainless life? Coral skeletons that have shown us how to create cement that sequesters pollution, or oysters that teach us how to restore coastlines, and what about the insights from jellyfish that are shaping the future of marine robots? Surely they are making a case at the United Nations annual climate summit known as COP, such as influencing COP15’s biodiversity plan to set aside ⅓ of land and ocean for biodiversity by 2030.

What if slime mold’s accomplishments took the spotlight at COP28 in Dubai and showed world leaders how nature is part of the solution–to help think beyond more obvious climate poster children like mangroves, forests and kelp? The work inspired by this organism could provide a radical rethink of what’s possible, viable implementation plans and concrete outcomes that can help transform a deeply vulnerable world in true crisis.

But what should we think about ourselves when we seek guidance from literal no-brainers?

We’re getting smarter.

We’re putting pride and egos aside, and the reward is intelligence only many millions of years of trial and error can provide. We’re learning that primitive can be synonymous with progress. Even institutions defined by power and deep pockets—(United Nations, NASA, governments, military), academia defined by intellect and innovation (MIT, CalTech, Harvard, Cambridge), and history-defining companies (Nike to Newlight)—are consistently turning to the slimy and the scaled because they result in the breakthroughs we need and have something – a hard-earned knowing spanning eons – we never could without them.

We’re seeing wild nature as more than a resource to be mined and more than a database masterclass for solving design or tech challenges, but a force that connects us — blobs to blood-relatives — to a greater, interconnected wonder-filled whole.

So here’s to being part of a world where even from the confines of a petri dish, the brainless transform our own private universes as they help us understand those light-years away.

About the author

Katie Losey is committed to bridging the gap between humans, nature’s genius, breakthrough innovations and overlooked wonder. She has worked at the intersection of business and conservation for two decades. In her work she has taken on many roles, including marketing director, writer, and strategist for companies in travel, conservation, nonprofit, and energy sectors. In these roles, she was further exposed to the possibilities of innovation inspired by nature from locking eyes with gorillas in Rwanda and swimming alongside orcas in Norway to dodging rats in NYC! Katie has been a member of The Explorers Club since 2015 and serves on their Public Lecture, Film and World Oceans Week Committees. She has been guest writing for the Biomimicry Institute since 2019, and her science writing has been featured in courses at the U of Cambridge, Johns Hopkins U, and on the cover story of the U of Richmond Magazine (her alma mater). She lives in NYC. Connect with Katie on Instagram and LinkedIn.