News & Updates

Updates from the Institute

Biomimicry Institute Launches their Inaugural Co-Lab focused on Buildings, Cities & Infrastructure

Biomimicry Institute Launches their Inaugural Co-Lab focused on Buildings, Cities & Infrastructure aimed to catalyze sector-wide shift toward nature-positive solutions.

A Year of Belonging: Reflections on Growth, Connection, and Nature’s Wisdom

As this year draws to a close, I find myself looking back over the past twelve months with an incredible sense of pride for what we have achieved. This year we stepped into the first…

Building a Future with Our Hands: What ‘Home’ Means in 2025

It’s late 2025, and a lot has changed since the most popular essay collection in AskNature’s history thus far, “How Does Nature Build a Home?“, was first published in early 2023. Back then, I was…

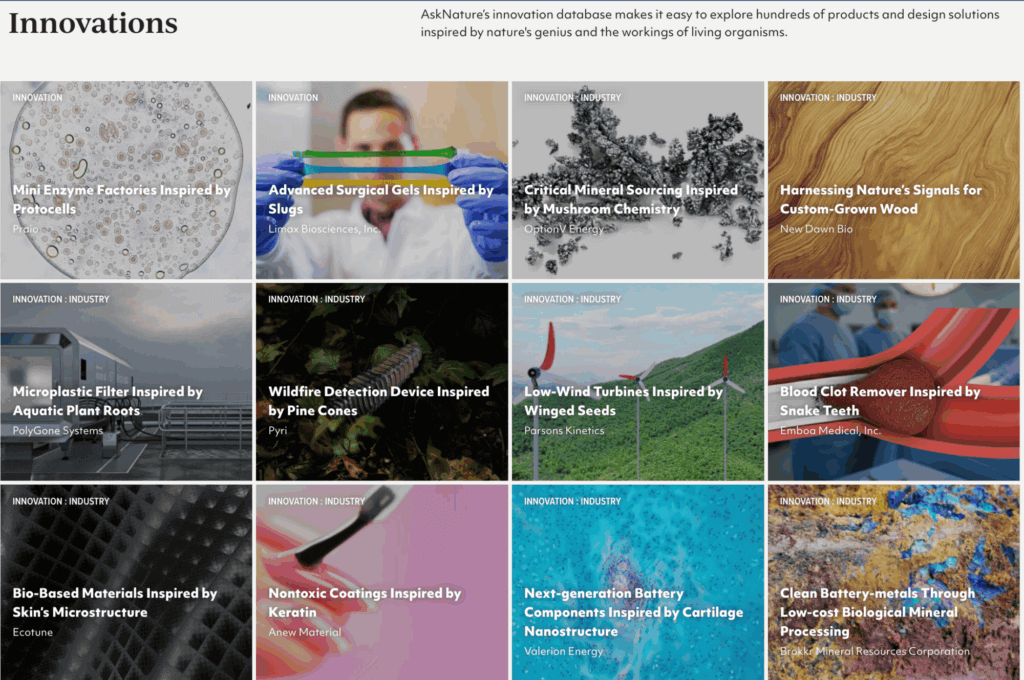

Ray of Hope Gallery 2025: Ten Nature-Inspired Innovations Now Live on AskNature

There is a phrase from Janine Benyus’s book Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature that has never left me: “Life creates conditions conducive to life.” In a moment when we urgently need systems that regenerate rather…

Upcoming events

Ray of Hope Accelerator Demo Day

Join us for this year’s Ray of Hope Accelerator Demo Day. A 90-minute interactive showcase of ten startups using nature’s strategies to solve some of the world’s most urgent challenges. After six months in our accelerator,…