SNAPSHOT

Name: Physarum polycephalum or slime mold/mould (translation: many headed slime)

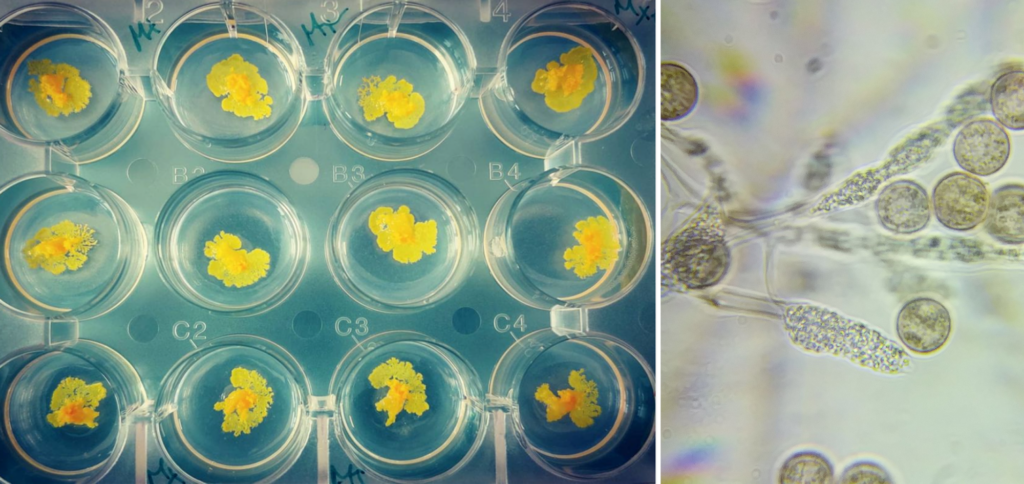

Organism type: Single-celled amoeba

Time on Earth: >500 million years

Favorite Food: Porridge oats

Dislikes: Salt, direct sunlight, caffeine, cold air

Problem solved: Generative design; mapping algorithms; urban planning; more efficient transportation, routing, energy grids, freight networks; better self-driving cars and robots

Behind the science: Toshiyuki Nakagaki, NASA, ESA, French National Centre for Scientific Research (CRNS), Hokkaido Univ., U of Toronto, Oxford Univ., New Jersey Institute of Technology SwarmLab, UWE Bristol, UC Santa Cruz, Harvard Univ., Tufts Univ., Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, ecoLogicStudio, United Nations Development Programme, PIX, Airbus, The Living, AutoDesk; Synthetic Landscape Lab at Innsbruck University, Urban Morphogenesis Lab at the Bartlett UCL

It’s been a consultant for NASA, shot at by police and mistaken for an alien. How slime mold—a brainless, single-celled organism—mapped the dark universe, keeps challenging the top minds to rethink what intelligence even is and has an ability to fill us with wonder beyond the human kind.

The world doesn’t know what to make of it.

Single-celled and as brainless as its name suggests, it’s one of the last organisms we’d expect would influence our beliefs on intelligence, intoxicate us with wonder, or enlighten us on the depths of the cosmos. But that’s what happened when slime mold creeped towards its lunch and unwittingly mapped the dark universe, demonstrating intelligence without a brain and, yet again, challenging what that word even means.

At first glance, no one would say slime mold is blessed with natural gifts. It doesn’t have a brain, not even a neuron. It also has no eyes, ears, mouth, legs, vocal cords, heartbeat or a single sensory organ. It remains one cell all its life. Remarkably, it can remember, make complex decisions, anticipate change, demonstrate altruism, recognize itself–and accomplish things we still can’t.

Despite having the same neuron count as a brick of cement (0), slime mold has 48,500 academic papers on Google Scholar.

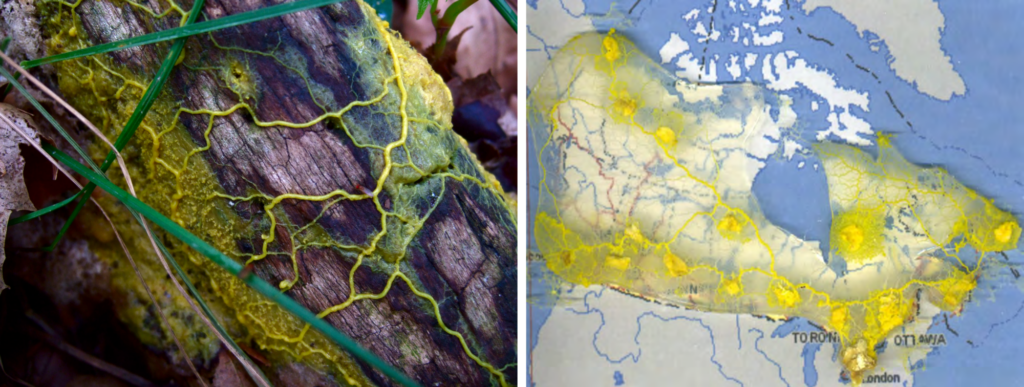

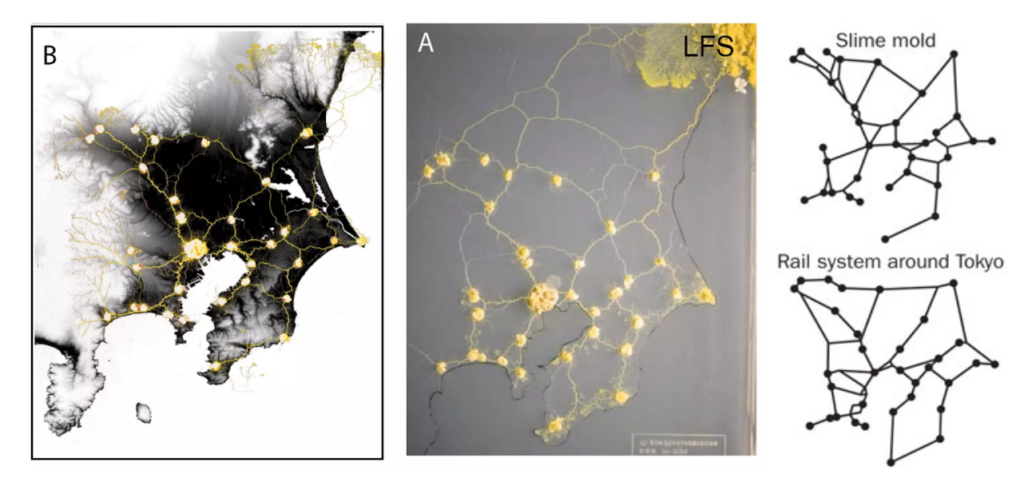

Search for “slime mold” on Google Scholar now, and you’ll likely find a significantly higher number of results (I’ve had to adjust it multiple times while writing this piece!). The research and real-world contributions that underpin the organism have a vital role in improving transportation routing (interstate highways, subway systems, urban planning) and building more efficient energy networks (power grids, undersea cables) to improving safety (search-and-rescue, evacuation routes) and collaborating on bio-inspired generative design (manufacturing, aerospace, cars, robotics, urban design). Slime mold keeps proving itself without trying or knowing, and luckily the world–academics, astrophysicists, artists, city planners, students–is paying attention.

After all, it mapped Tokyo’s rail system in 26 hours–something that took humans a century to master. Plus, its intel isn’t limited to our home planet; slime mold’s visit to the International Space Station led to discoveries on microgravity and its algorithms are helping trace the dark cosmos–informing top thinkers at NASA, ESA, CNES and beyond on some of the most perplexing parts of our universe.

We think of kids and pets requiring babysitters and loved ones by our side on vacation, but blobs get packed up too! If left unchecked their wild sides can be unleashed, like when Dr. Audrey Dussutour, a French researcher, found her gooey specimens had ditched their individual petri dishes to hang as a massive blob from the lab ceiling instead! Member posts like “Escape attempt” are speckled throughout the Slime Mould Collective (an international network on the organism) and the University of Warwick even has a Slime Troubleshooting section of their website which says something in itself!

How can they be this naughty with ZERO neurons?! To put it in perspective, humans have > 80 billion neurons, honeybees > 1 billion neurons, and slime mold have none. It’s impossible not to be impressed.

So while primative and prehistoric, slime mold’s accomplishments are beyond our abilities—proof of an intelligence beyond the human kind and the wonder laced everywhere, even the last places or lifeforms we’d think to look.

Maybe these blobs show how much more closely we’re related to the most unrelatable, and how everything is interconnected: cells to cities to the cosmos.

Or perhaps, for something whose given name suggests “ick, avoid” and is simply incorrect (it’s not mold, it’s an amoeba), what that really shows is that the limited thinking here has been our own. Anyone reading this sentence is proof that’s changing.

This is the first part of our 8-edition blog series on slime mold by guest writer Katie Losey. She answers your top questions on this fascinating organisms and dives into how a brainless, single cell is capable of shaping our futures and blowing our minds. Read part 2 “Slime Mold 101: Meet the Genius Without a Brain” here.

Main image credit: Nik Arthur’s research pieces – commissioned work by Dominic Fike for his new album.

About the author

Katie Losey is committed to bridging the gap between humans, nature’s genius, breakthrough innovations and overlooked wonder. She has worked at the intersection of business and conservation for two decades. In her work she has taken on many roles, including marketing director, writer, and strategist for companies in travel, conservation, nonprofit, and energy sectors. In these roles, she was further exposed to the possibilities of innovation inspired by nature from locking eyes with gorillas in Rwanda and swimming alongside orcas in Norway to dodging rats in NYC! Katie has been a member of The Explorers Club since 2015 and serves on their Public Lecture, Film and World Oceans Week Committees. She has been guest writing for the Biomimicry Institute since 2019, and her science writing has been featured in courses at the U of Cambridge, Johns Hopkins U, and on the cover story of the U of Richmond Magazine (her alma mater). She lives in NYC. Connect with Katie on Instagram and LinkedIn.