It’s been a consultant for NASA, shot at by police and mistaken for an alien. How slime mold–a brainless, single-celled organism–mapped the dark universe, keeps challenging the top minds to rethink what intelligence even is and has an ability to fill us with wonder beyond the human kind.

Slime mold’s party tricks are proving to be laced with valuable intel we wouldn’t have without them.

For many, their intro to this yellow goo was watching it solve puzzles more efficiently than Harvard grad students. But their tricks creep way beyond maze walls.

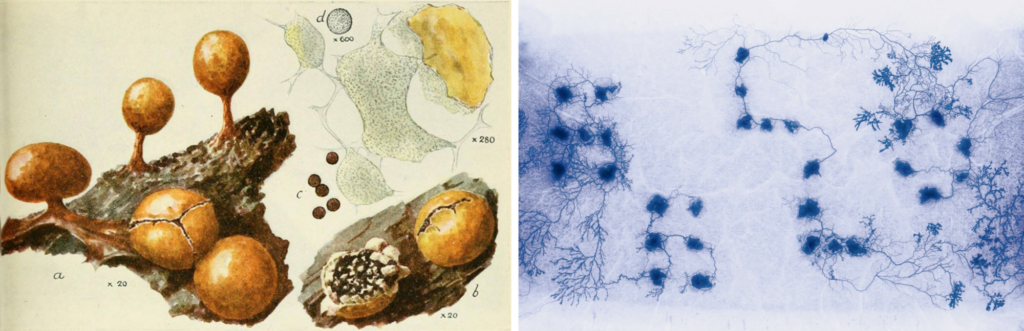

For starters, there are > 900 types and 720 sexes. Its official name is Physarum polycephalum (translation: many headed slime) and while the organism starts life with a spore, it’s not mold, a fungus, plant or animal. Slime mold is an amoeba–an ancient form of life–and a classification that took scientists a long time to come to (initially they were misclassified as fungi, hence their nickname).

Where they lack a brain, they ooze with charm.

This seemingly unremarkable stuff survived extinctions the more obviously magnificent didn’t. Older than the dinosaurs with a range that goes from the arctic to deserts and jungles to cities, these guys have lived across space and time. Certain slime molds can be hard to see, others hard not to—some individuals can take over half a tennis court! That is possible when a slime mold fuses together with others–and others, and others–becoming a supercell. Still one cell, each with their own genetic material, but with membranes that break down allowing limitless nuclei to float freely within the same “body” (if you can call it that). An interesting aside: even though the cells aren’t related, their decisions are known to benefit the entire group, an altruistic social behavior being studied by scientists.

They are maybe the last lifeform to vie for our approval or desire our attention, but they manage to earn both.

Perhaps you’re one of its > 64 million viewers on TikTok, discovered them in Heather Barnett’s astounding TedTalk, saw their recommended road map for the US interstate and the Tokyo rail system, grasped their delicate beauty in this tribute or this lovely one, or watched the delightful 10-min doc Breakthrough: The Slime Minder where Dr. Dussutour explored how cognition may not be limited to animals and that individual slime mold strains can have their own “personalities” (apparently Americans can be quite difficult!). Did you hear they solved a maze more efficiently than Harvard grad students, can play video games, ran a computer, inspired their own comic book or choreographed a dance, starred all over Euphoria star Dominic Fike’s new track, prompted new ways of driving cooperation in urban communities, can transfer knowledge to friends, creeped their way into homes of the French, joined the college faculty as a non-human scholar, can anticipate events, and some types are helping researchers understand the way cancer grows? The one named “le Blob” got an exhibit at a Paris zoo and others received a special invite to the International Space Station to take part in an epic classroom project. I’m slime mold obsessed myself; since researching this series I find myself bringing up slime mold in random conversation when I don’t need to and I recently joined the Slime Mould Collective, a network whose very existence is uplifting. Member posts like “Escape attempt!” and “Enteridium lycoperdon or giant zit?” are a refreshing departure out of the world of cryptocurrency and celebrity brands and into another one maybe we didn’t know we needed.

Have you come across “dog vomit” yet?

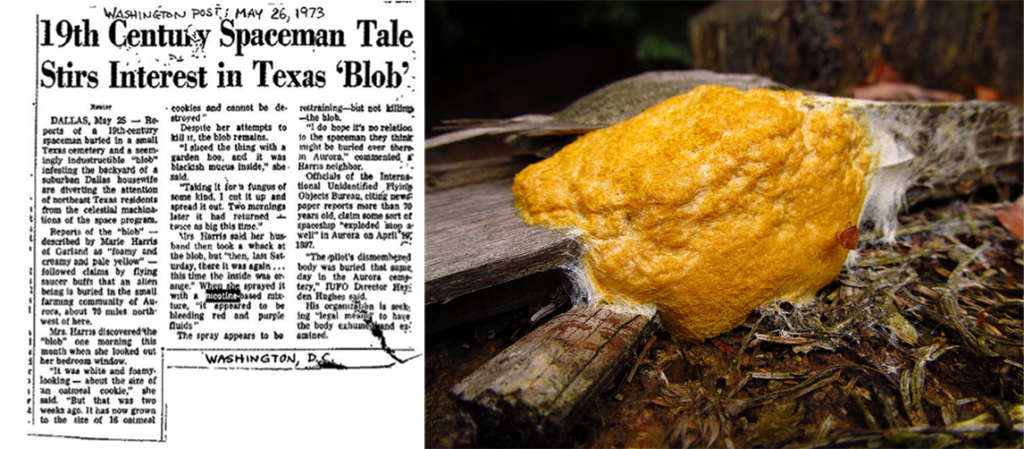

It’s possible you’ve noticed these yellow creepers on a rotting log or decomposing the forest floor. Or maybe you’ve been lucky enough to come across the type nicknamed “dog vomit” – you’d know if you had! Other terms of endearment include “living creepies,” “demon droppings” by Chinese scholar Twang Ching-Shih, and “rotting mucus” by Carl Linnaeus (whose nickname “Father of Taxonomy” was a bit more respectable).

Good story: Rewind to 1973 when a woman from the Dallas suburbs noticed “dog vomit” slime mold in her yard. She was so repulsed she wanted to kill it, so she wacked it with a garden hoe. Overnight it grew back even bigger. She tried to poison it, but it came back the next day. She called the police who shot it and the fire department who pummeled it with a firehose, but it survived. Eventually it seemed to disappear. In reality it didn’t; this was during its sporation phase, but the woman wasn’t aware of the organism nonetheless this phase of its life. Later she claimed she was visited by an alien which was printed in The Washington Post.

Party tricks got our attention, but slime molds haven’t pulled off their biggest stunts yet.

Their ability to delight is partly a symptom of their uncanny ability to find the most direct path without distraction. And it’s this enviable skill that benefits us all, and why the most resourced and intelligent amongst us are looking to goo for answers anchoring life-changing, planet-balancing innovations. They contribute valuable intel, a brighter path forward and a heavy dose of wonder that we wouldn’t have without them.

Slime mold unleashes creativity! Here, digital simulations mimic Physarum Polycephalum, generating real-time patterns and dynamically reacting to human interactions in large-scale projections. | Uncharted Limbo Collective

For those who have actively moved towards and work with slime mold, oftentimes they learn to know their unique curiosities, tendencies and preferences by heart. Makes sense that pet slime mold is a thing; that one of their first champions and the world expert at the time, biologist and botanist Gulielma Lister (known as the Queen of Slime Moulds) devotedly studied and sketched them even back in the early 1900s; and that introverts to extroverts to astronauts to artists admit they can get attached to individual specimens.

Now seems like a good time for Anaïs Nin’s words, “It is a sign of great inner insecurity to be hostile to the unfamiliar.” Like many new encounters, meeting an “other” is also an invitation towards a different side of ourselves. It’s up to us whether we get out the garden hoe or get curious.

This is Part 2 of our 8-edition blog series on slime mold by guest writer Katie Losey. She answers your top questions on this fascinating organism and dives into how a brainless, single cell is capable of shaping our futures and blowing our minds. Read Part 3 “Watch a No-Brained Blob Think Out Loud” here.

Feature photo: Slime mold turned heads when it solved mazes more efficiently than Harvard grad students | Image: PBS Digital Studios

About the author

Katie Losey is committed to bridging the gap between humans, nature’s genius, breakthrough innovations and overlooked wonder. She has worked at the intersection of business and conservation for two decades. In her work she has taken on many roles, including marketing director, writer, and strategist for companies in travel, conservation, nonprofit, and energy sectors. In these roles, she was further exposed to the possibilities of innovation inspired by nature from locking eyes with gorillas in Rwanda and swimming alongside orcas in Norway to dodging rats in NYC! Katie has been a member of The Explorers Club since 2015 and serves on their Public Lecture, Film and World Oceans Week Committees. She has been guest writing for the Biomimicry Institute since 2019, and her science writing has been featured in courses at the U of Cambridge, Johns Hopkins U, and on the cover story of the U of Richmond Magazine (her alma mater). She lives in NYC. Connect with Katie on Instagram and LinkedIn.