As the examples on AskNature.org show us, the natural world is full of wisdom that has led to innovations across countless disciplines. Again and again, we find nature serves as a source of inspiration when solving well-defined design problems.

“Well-defined” is key here. Architects, engineers, and inventors all start the biomimicry design process by first defining the problem they want to solve. Only then can they look to nature to learn how similar problems have been solved before.

But what happens when we struggle to define our area of focus? What happens when it’s difficult to define the problem?

This is something business owners face all the time. When growing an organization, there are always multiple strains on our time and attention. There is always a myriad of problems to solve, and dozens of potential paths to take.

Do we focus on bringing in new customers? Or better serving existing customers? Do we spend more money on marketing? Developing new products? Better products? What is the opportunity cost of focusing on one problem over another? Where do we focus next for the greatest returns?

These are the questions most business owners struggle with on a daily basis. In fact, a lot of the stress of growing a business often arises from this basic conflict. Not knowing which problem is most worth solving, feeling like our attention is being pulled in multiple directions at once.

Apart from inspiring innovation, few know that nature can also help us define our areas of focus. Outside of well-defined design challenges, the natural world can also help reveal the areas of leverage inside our businesses.

When we look at some of the fundamental patterns that exist in nature, we can see that these also exist in other systems. A business, which shares the similar basic objective of growth, is one of these. By understanding how the areas of leverage in our businesses mimic those found in nature, we can avoid that feeling of being pulled in multiple directions at once.

It can help us determine where to best focus our time and energy for the greatest returns. We can regain a sense of confidence we’re moving in the right direction, and know that the problem we’ve chosen to solve is the right one.

Natural Orders

In the book On Growth and Form, Scottish mathematician D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson described the mathematics underlying dozens of natural phenomena: the formation of cells, the relationship between size and weight in animals, the rates of growth in trees, and many others.

The book is now considered a classic, being instrumental in the development of the field of allometry: the study of the relationships between animal body size and shape, anatomy, physiology, and behavior. But On Growth and Form’s influence extends even further than the creation of its own field.

Since its publication in 1917, it’s been regularly prescribed as required reading in many undergraduate architecture courses, and influenced the work of dozens of prominent figures, from biologist Conrad Hal Waddington, to computer scientist Alan Turing and anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss.

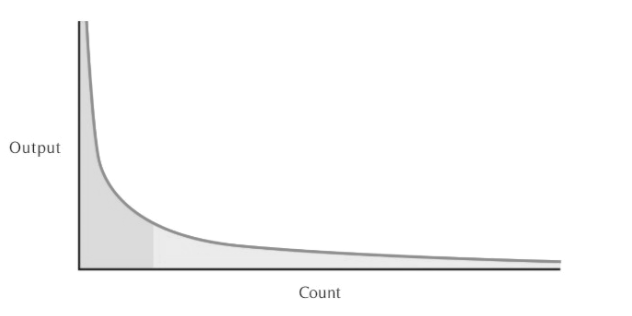

By using mathematics to describe nature, Thompson reveals certain patterns seem to appear more common than others. As he describes the natural phenomena in his book, one in particular stands out as most prevalent: the “power law distribution”:

Power Law Distribution: The minority of instances account for the majority of output.

Looking at the graph above, this “L-curve”, as it’s sometimes referred to, has a few defining features:

- A “Tall Head” on the left side, where a minority of total measurements cluster together, but together produce the largest results.

- A “Long Tail” trailing out towards the right, where the majority of the measurements create diminishing results.

This one distribution describes so many of the patterns of distribution we find in nature. They are so ubiquitous; and once you read some examples, you’ll begin to see this basic pattern repeated everywhere you look:

- Rainforests comprise just 6% of global landmass, but contribute 50% of the world’s biodiversity.1

- 80% of all known species on earth are insects (arthropods), and all other life makes up the other 20%.2

- Of these insects, 80% of all insects are beetles, 20% are all other insects.3

- 20% of those infected with a disease account for 80% of its spread.4

- 2% of Earth’s surface area is home to 50% of all plants and animals.5

- 20% of bird species make up 80% of sightings.6

- 1.4% of tree species account for 50% of trees species in the Amazon Rainforest.7

- 80% of a tree’s branches produce 20% of the leaves, and 20% of the branches produce 80% of the leaves.

- 20% of words in a language accounts for 80% of usage.8

Power laws are something akin to a “Law of Nature”, as far as we can say we have anything like that at all. At the very least, it’s a very common pattern that in some ways describes the way our world is organized.

Power Laws in Business

These sorts of distributions aren’t just limited to the natural world, they’re also ubiquitous in business. The typical applications of biomimetic design are often found in more practical examples: engineering, technology, and product design.

But the patterns of nature reveal lessons that can be applied to concepts that, while slightly more abstract, ultimately lead to huge benefits for those in business.

By applying the power law distributions found in nature to your business, you’ll be able to be more efficient with your time, and focus on the most effective areas to grow your business.

In his book 80-20 Sales and Marketing9, Author and Consultant Perry Marshall applies these power laws to a business context. In the book, Marshall identifies how one type of power law, namely the 80-20 distribution, or Pareto Principle, is particularly common.

This instance of a power law distribution, the “80-20”, originally takes its name from the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, who first noticed a peculiar pattern in the distribution of wealth in Italy. Specifically, he noticed that roughly 80% of total land ownership was attributable to only around 20% of the population.

Throughout the book, Marshall often repeats the maxim “80% of results come from 20% of effort”. What he means is that if you can find the “Tall Head” that produces the majority of results, you can then focus on those elements to create more of that result.

This is a helpful concept to understand, because many of the distributions you’ll find in your business follow this power law curve, just like the ratio shared between limbs, branches, and leaves on a tree. Look at some other examples of the 80-20 principle in business, and this becomes even more apparent:

- 20% of sales people are responsible for 80% of total sales revenue. If you have ten sales people, only two of those are going to be star performers, closing the most deals.

- 20% of customers account for 80% of total profits. Ten customers, two of those the business cannot afford to lose – a very common situation. Double down on creating a standout experience for these customers, and update your marketing to target more people of their exact type.

- 20% of the most reported software bugs cause 80% of software crashes. Software companies typically have long lists of bugs and user-reported issues. By noting the most commonly reported issues, time can be saved and a better user experience can be provided.

- 80% of customers only use 20% of software features. Similar to the above, by noting how users interact with your product, many technology business owners find that the majority of the value their tool provides is attributable to a relatively small feature they may have previously not acknowledged.

- 80% of your complaints come from 20% of your customers. An easy way to win back your sanity if things seem crazy is to keep this one in mind. Sometimes it’s easier to say goodbye to a small handful of problem customers that are causing the most problems.

By understanding the overlap between the patterns of nature and our businesses, we can identify the highest leverage opportunities available to us. It can help us to define the problem we actually want to solve.

By understanding the way nature organizes the world, you’ll begin to see its patterns everywhere you look. How does the power law distribution apply to your business?

Need help finding inspiration? Head to AskNature.org and see if there are answers already waiting for you.

As a marketing consultant with a background in Ecology, Matt Treacey knows what it takes to build systems designed for growth. With a focus on email marketing automation, at Symbios Growth Automation Matt takes an analytical approach to help grow revenue for eCommerce stores and SaaS startups across the US and Oceania. Matt’s writing helps founders discover how they can draw from nature to build simpler, more profitable online businesses.

As a marketing consultant with a background in Ecology, Matt Treacey knows what it takes to build systems designed for growth. With a focus on email marketing automation, at Symbios Growth Automation Matt takes an analytical approach to help grow revenue for eCommerce stores and SaaS startups across the US and Oceania. Matt’s writing helps founders discover how they can draw from nature to build simpler, more profitable online businesses.

References:

- Nunez, Christina. “Rainforest and Amazon Facts and Information.” National Geographic, National Geographic, 15 May 2019, www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/rain-forests.

- Janzen, D. 1976. Why are there so many species of insects? Proceedings of XV International Congress of Entomology, 1976: 8494.

- Pennak, Sarah, and Quentin Wheeler. State of Observed Species: Report Card on Our Knowledge of Earth’s Species. 2011th ed., Arizona State University, International Institute of Species Exploration, 2012, www.esf.edu/species/documents/sos2011.pdf.

- Cooper, L., Kang, S.Y., Bisanzio, D. et al. Pareto rules for malaria super-spreaders and super-spreading. Nat Commun 10, 3939 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11861-y

- Bradford, Alina. “Facts About Rainforests.” Livescience.Com, 28 July 2018, www.livescience.com/63196-rainforest-facts.html.

- Rispoli, Fred J., et al. “Even Birds Follow Pareto’s 80-20 Rule.” Significance, vol. 11, no. 1, 2014, pp. 37–38. Crossref, doi:10.1111/j.1740-9713.2014.00725.x.

- Steege, H. ter, et al. “Hyperdominance in the Amazonian Tree Flora.” Science, vol. 342, no. 6156, 2013, p. 1243092. Crossref, doi:10.1126/science.1243092.

- Newman, MEJ. “Power Laws, Pareto Distributions and Zipf’s Law.” Contemporary Physics, vol. 46, no. 5, 2005, pp. 323–51. Crossref, doi:10.1080/00107510500052444. Available.

- Marshall, Perry, and Richard Koch. 80/20 Sales and Marketing: The Definitive Guide to Working Less and Making More. Illustrated, Entrepreneur Press, 2013.