Image courtesy of Cambridge Judge Business School

“I think the biggest innovations of the twenty-first century will be at the intersection of biology and technology.”

– Steve Jobs

“In God’s wildness lies the hope of the world.”

– John Muir

In an article I wrote here on Asking Nature in July, I shared my journey with 30 Days of Reconnection. Since then, I’ve been looking for ways to apply more of what I’m learning from the Biomimicry Institute. Discovering the ideas of Jobs and Muir inspired me to explore a concept I’ve been tossing around now for a while: trash!

I officially started my junior year in high school last month. A few years ago, when my older sister and I started dreaming about what we would do when we get older, I told her: “I want to be CEO of a trash company and help get the world’s garbage under control!” Even as a child, I thought about the ways we could be better in supporting our planet. But now, I realize it’s not only about figuring out the trash problem, it’s also about shifting our focus on making more of what we really need, minimizing the use of things we don’t need, and all the while maintaining an intention of doing less damage to the planet.

When contemplating a different approach to getting trash under control, I thought the answer must be related to the intersection of biology and design. It’s clear this intersection is becoming a popular topic: a 2015 TED Talk by Neri Oxman on the subject has more than 2.5 million views. And so, I started with the hypothesis that maybe the solution for our global trash troubles might be a designer organism, built with synthetic biology, inspired by the ethics of biomimicry.

Not Just Talking Trash

When I thought about a new kind of trash company that could clean up the planet, I learned there is a challenge that goes far beyond capturing refuse. To solve the problem, we must consider lots of variables in this giant equation. So, I started to make a list.

First, product producers and the materials they use will need to change. I looked for ways that materials science might use fewer resources to make things along the supply chain. One area that really captivated my attention was the Materials Genome Initiative, which finds new solutions to old trash problems. Just imagine creating new kinds of protein-based biosensors programmed to do their jobs that eventually decompose! We could create new types of recyclable plastics made from excess carbon dioxide. The possibilities are basically limitless, and that’s actually a bit of a problem when you’re trying to narrow things down!

A second variable I thought about is the potential for dematerialization. According to the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, products can be dematerialized in three ways:

- “Optimize – by reducing the mass or material types in the product

- Digitize – sell the product electronically or virtually

- Servitize – sell the utility of the product as a service”

A great example of dematerialization is the iPhone. Ten years before its introduction, the equivalent functionality would have required a dedicated phone, computer, camera, video camera, watch, and gaming console, just to name a few. Ten years from now, we can only imagine which devices will be the next to dematerialize. Production and disposal of the iPhone has its issues, but its negative impact is getting smaller.

As my trash ideas expanded, I felt less sure about how my company would work. The simple dream was getting complicated and losing its charm. I needed a way to hold onto my idea. That’s when I found the Biomimicry Design Toolbox.

The Biomimicry Design Toolbox

The Biomimicry Design Toolbox is “a set of tools and core concepts that can help problem-solvers from any discipline begin to incorporate insights from nature into their solutions.” I sampled some of it and I have to say, it’s powerful!

Using the toolbox gave me a process to think differently about the trash problem. My question started as “How can I help create a new kind of trash company?”, but that quickly changed. That’s OK, but the first thing I learned was that it’s better to use an iterative process if you want to learn from nature how to solve a problem.

The toolbox process starts with functions. In biomimicry, function describes an organism’s purpose and the way it does something. By comparing our design goals with nature’s functions and putting them into context, we can start tapping into 3.8 billion years of nature’s strategy catalog.

As a designer looking for ideas in nature, I followed the process and asked myself “What do I want my trash company design to do?” and “How does nature prevent waste from getting out of control?” By studying the toolbox, I learned that life on earth is a system where everything is connected.

Then, I thought again about our mountains of trash. Where does it come from? Where does it all go? I searched Asknature.org to find one organism with special functions that I could introduce to help get trash under control. But in nature, there is no trash: everything that it creates eventually gets reused or becomes part of another system. While I could look to decomposers, like mycelium, I wanted a different approach. And that’s when I got my big idea!

Shifting from Linear to Circular Systems

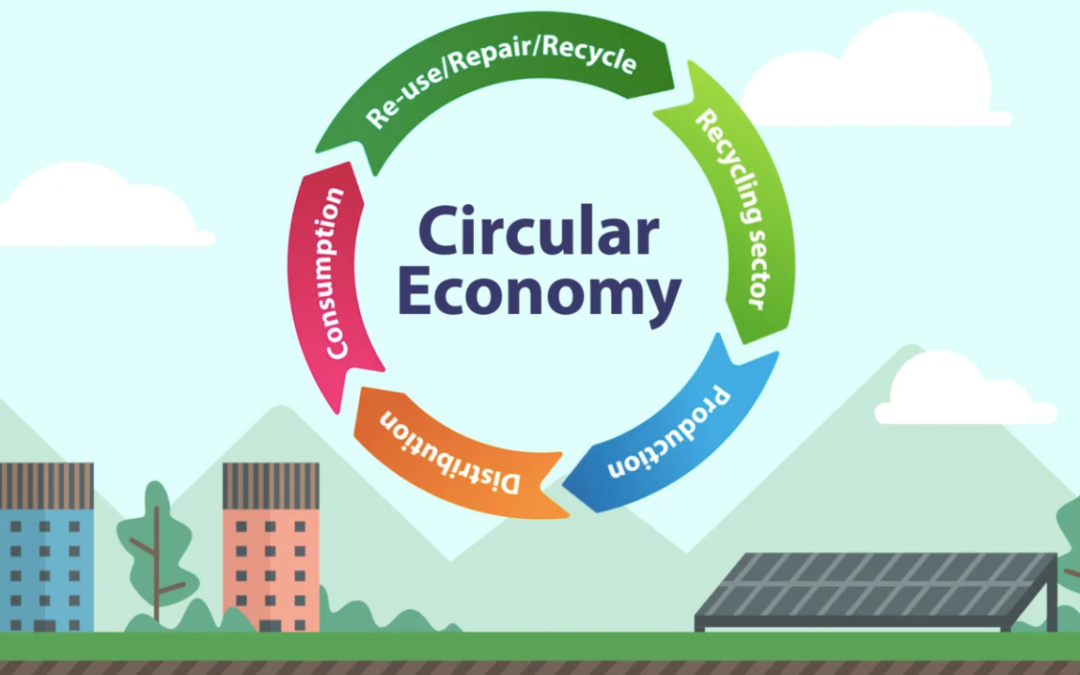

The big idea that hit me suddenly was that if we want to get trash under control and to stop destroying our environment at an insane rate, maybe we need our own circular system, where everything is a nutrient to something else and nothing is seen as waste — just like in nature. Turns out I’m not the first person to think like this, and that’s how I discovered “the circular economy”.

According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, unlike today’s linear model where resources are extracted, produced, and eventually trashed, a circular economy is “restorative and regenerative by design… based on three principles:

- Design out waste and pollution

- Keep products and materials in use

- Regenerate natural systems”

To me, this circular approach makes more sense than only redesigning materials, because it gives us the opportunity to rethink the whole system and at all stages of use. It’s bigger than the idea of “a new kind of trash company” that would still be stuck in today’s unsustainable linear system.

Rethinking the Whole System: A Clean Start

New materials, synthetic biology, and a circular economy are still in their early stages. As with any exponential technology, trends start small before taking off. There are dozens of design competitions around the world like Circular Economy 2030, OPENIDEO, Solve by MIT, and of course, the Biomimicry Global Design Challenge, among many others. I am optimistic that a circular economy is achievable in our lifetime.

Looking back on the last few weeks, I see that everything is the result of a design, whether it’s accidental, deliberate, or divine. What started as a reflection exercise and a notebook sitting next to rows of tomato plants has grown into an awareness of what a really different future could look like. Going through this process showed me how the combined powers of science, technology, and design just might be enough to help us meet the ultimate challenge: shifting from the “take, make, and waste” world we’re living in today into a new kind of economy that is healthier, more sustainable, and better for all of us by design.

Sophia Stiles is a high school student based in California. In her free time she enjoys drawing and taking walks with her family.

Sophia Stiles is a high school student based in California. In her free time she enjoys drawing and taking walks with her family.